He spent the twilight of his career denouncing Donald Trump as a threat to the republic he loved. But Dick Cheney arguably laid the foundations of Trump’s authoritarian takeover of the United States.

The former vice-president died on Monday aged 84. The White House lowered flags to half-mast in remembrance of him but without the usual announcement or proclamation praising the deceased.

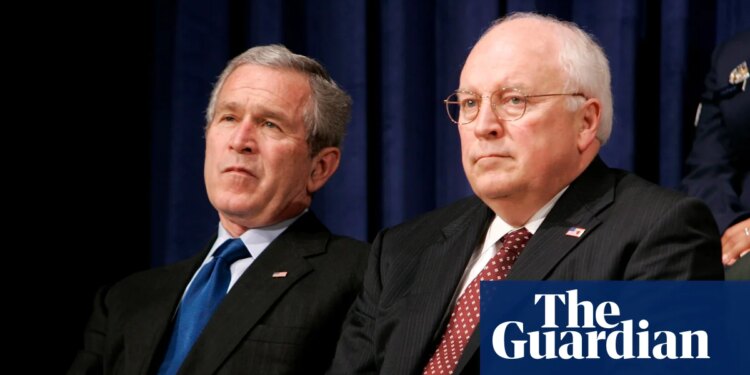

Cheney, who served under George W Bush for eight years, was one of the most influential and polarising vice-presidents in US history. Some critics said they would never forgive him for pushing the US to invade Iraq on a false pretext but suggested that his opposition to Trump offered a measure of redemption.

Perhaps Cheney’s defining legacy, however, was the expansion of powers for a position that he never held himself: the presidency. Cheney used the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks as a pretext to assert a muscular executive authority that Trump now amplifies and exploits to challenge the system of checks and balances.

Some commentators perceive a direct through-line from the Bush-Cheney administration’s policies – such as pre-emptive war, warrantless spying and the creation of novel legal categories like “enemy combatant” – to the Trump administration’s actions against immigrants, narco-traffickers and domestic political opponents.

“Dick Cheney is the godfather of the Trump presidency,” said Larry Jacobs, director of the Center for the Study of Politics and Governance at the University of Minnesota. “Trump is unchained because Dick Cheney had been at war for half a century against the restraints put in place after Vietnam and Watergate. He believed that action was more important than following constitutional rules.”

The debate over the balance of power between the White House, Congress and courts did not start with Cheney. In 1973, the historian Arthur Schlesinger Jr published The Imperial Presidency, arguing that the executive branch had begun to resemble a monarch that often acted without the consent of Congress.

However, by the time of the Ronald Reagan administration, young conservatives felt the presidency had become hamstrung. This sentiment culminated in a 1989 American Enterprise Institute volume titled The Fettered Presidency, articulating a doctrine to regain what they saw as constitutionally appropriate powers.

As a young chief of staff in the Gerald Ford administration, Cheney experienced the fallout of the Watergate scandal. He concluded that a sceptical Congress, reacting to the abuses of Richard Nixon, had gone too far, leaving the presidency dangerously weakened.

Jacobs said: “Dick Cheney took it as his mission to tear all that down. He saw the efforts to return accountability in the 70s after Watergate and Vietnam as profoundly and dangerously limiting presidential power. He talked openly about Congress self-aggrandising and warned that the country would face ruin.”

Cheney believed that new constraints such as the War Powers Act, a 1973 law that limited the president’s power to commit US forces to conflict without congressional approval, had hobbled the executive, making it nearly impossible for a president to govern effectively, particularly in national security.

In a 2005 interview, he said: “I do have the view that over the years there had been an erosion of presidential power and authority, that it’s reflected in a number of developments – the War Powers Act … I am one of those who believe that was an infringement upon the authority of the president.

“A lot of the things around Watergate and Vietnam, both, in the 70s served to erode the authority, I think, the president needs to be effective especially in a national security area.”

Cheney’s ideas were formalised as the “unitary executive theory”, which asserts that the president should possess total and personal control over the entire executive branch. This effectively eliminates the independence of a vast array of government institutions and places millions of federal employees under the president’s authority to hire and fire at will.

As Bush’s No 2, Cheney was dubbed “Darth Vader”. When America was attacked on 9/11 with nearly 3,000 people killed, the trauma created a political climate in which extraordinary measures were deemed necessary. Cheney turned a crisis into an opportunity to broaden executive power in the name of national security.

He was the most prominent booster of the Patriot Act, the law enacted nearly unanimously after 9/11 that granted the government sweeping surveillance powers. He championed a National Security Agency warrantless wiretapping programme aimed at intercepting international communications of suspected terrorists in the US, despite concerns over its legality.

The Bush administration also authorised the US military to attack enemy combatants acting on behalf of terrorist organisations, prompting questions about the legality of killing or detaining people without prosecution at sites such as Guantánamo Bay and Abu Ghraib.

This doctrine is now being used by the Trump administration to justify deadly strikes on alleged drug-running boats in Latin America. It claims the US is engaged in “armed conflict” with drug cartels and has declared them unlawful combatants.

Last month the Pentagon chief, Pete Hegseth, wrote on social media: “These narco-terrorists have killed more Americans than al-Qaida, and they will be treated the same. We will track them, we will network them, and then, we will hunt and kill them.”

In 2002 a set of legal memorandums known as the “torture memos” were drafted by John Yoo, deputy assistant attorney general, advising that the use of enhanced interrogation techniques might be legally permissible under an expansive interpretation of presidential authority during the “war on terror”.

Jeremy Varon, author of Our Grief Is Not a Cry for War: The Movement to Stop the War on Terror, said: “That championed the unitary executive theory and then said as an explicit argument anything ordered by the commander in chief is by definition legal because the president is the sovereign.

skip past newsletter promotion

Sign up to This Week in Trumpland

A deep dive into the policies, controversies and oddities surrounding the Trump administration

Privacy Notice: Newsletters may contain information about charities, online ads, and content funded by outside parties. If you do not have an account, we will create a guest account for you on theguardian.com to send you this newsletter. You can complete full registration at any time. For more information about how we use your data see our Privacy Policy. We use Google reCaptcha to protect our website and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

after newsletter promotion

“In its own day it was considered a dubious if not a highly contestable legal theory, but the Trump administration is almost pretending that it’s settled law and then using expansive ‘war on terror’ powers to create a war on immigrants, a war on narco traffickers and even potentially a war on dissenting Americans as they protest in the streets.”

Varon, a history professor at the New School for Social Research in New York, added: “The great irony is that Trump represents, on the one hand, the repudiation of the neoliberal neocon globalists like Cheney and Bush that entangled America in forever wars. But now America First is being weaponised, making use of ‘war on terror’ powers to capture, brutalise, dehumanise and kill people without any sense of legal constraint.”

As an architect of the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, Cheney pushed spy agencies to find evidence to justify military action. He asserted that then Iraqi president Saddam Hussein was developing weapons of mass destruction and had ties to the al-Qaida terrorist network. Officials used that to sell the war to members of Congress and the media, though that claim was later debunked.

The government’s arguments for war fuelled a distrust among many Americans that resonates today with some in the current Republican party. But it did not lead to a significant pushback from Congress aimed at preventing future presidents making a similar mistake.

The trend for executive power has been fuelled by an increasingly polarised and paralysed Congress, creating a vacuum that successive administrations, including those of Barack Obama and Joe Biden, have filled with executive action, unwilling to cede powers once gained.

The ultimate battle for the unitary executive theory is now being waged within the chambers of the supreme court. Recent rulings from the court’s conservative majority signal a shift away from longstanding precedents that have, for nearly a century, placed limits on presidential authority.

Since taking office in January, Trump has unleashed a barrage of unilateral presidential actions. He has waged a campaign to remove thousands of career government workers from their posts and shut down entire federal agencies. His deployment of national guard troops to major US cities and attacks on law firms, media organisations and universities have earned comparison with autocrats around the world.

Cheney himself did not approve. He became a severe and outspoken critic of Trump, arguing that the president’s actions went “well beyond their due bounds”, particularly regarding the integrity of the US electoral system. His daughter, Liz Cheney, became one of the most prominent opponents of Trump within the Republican party but eventually lost her seat in the House.

Ken Adelman, a former US diplomat who knew Cheney since working with him the 1970s, was not surprised that he took a stand. He said: “Trump stood for everything Dick did not stand for and that was foreign policy, you support your friends and you oppose the totalitarians, strong alliances, strong defence and free trade.

“He was very uncomfortable and then finally turned and absolutely opposed Donald Trump with every fibre of his bone, which shows that conservatives can oppose Trump and should oppose Trump because he’s not conservative and he’s not decent and he’s not honourable.”

Some commentators contend that while Cheney operated to enhance the power of the institution of the presidency for policy and national security reasons, Trump has leveraged that power for self-aggrandisement, pushing beyond boundaries that Cheney himself recognised.

Robert Schmuhl, a professor emeritus of American studies at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana, said: “Clearly in his time as vice-president, he pushed that envelope almost as far as anyone could. But the distinction is that Cheney was trying to enhance the power of the presidency for policy and security reasons, while Donald Trump seems to be pushing for greater power in the presidency that also has a personal dimension for him.”

Others agree that, along with the rhymes between Cheney and Trump, there are significant differences. Jake Bernstein, co-author of Vice: Dick Cheney and the Hijacking of the American Presidency, said: “You can draw a line between Cheney and Trump. Trump has taken that to the max; as they say in Spın̈al Tap, he’s turned it to 11. It’s a qualitative difference.

“Yes, Cheney believed that power had tilted too much towards Congress and had to go back to the executive and certainly believed that, particularly in issues of war-making, the executive should be completely unfettered. He also understood a lot of this balance between Congress and the executive was based on norms that were elastic and could be stretched in one direction or another.

“But he was absolutely at heart an institutionalist and he didn’t want to break those norms. He didn’t want to destroy those institutions. He would have been appalled by the neutering of Congress that’s going on under this current Trump administration. Basically Trump is president and speaker of the House at the moment, and that would have offended Cheney.”