Kalif Raymond has played for the Lions since 2021, but he became a Lion before that. From 2016 to ’18, Raymond was released five times by four franchises. Well, he was an undrafted 5’8″ receiver/returner from Holy Cross. Those guys get cut. He says now that, “No matter what, there’s gonna be a bubble of preconceived notion” because of his height. But then he says this:

“It is not their job to see it any differently. It’s my job to show them that they’re wrong.”

Raymond says, “I was always getting cut for a reason, and it was never the same reason twice.”

He did what so many players do not: He assumed the coaches who cut him were right. Then he got to work. The goal was to eliminate every one of those reasons, so some team had to keep him.

Raymond finally stuck with the Titans. He returned kicks and punts, and caught 18 passes in two seasons. On one play, against the Colts, he ran a route so perfectly that he thought, “Man, I can do it.” The play didn’t even result in a reception. But it was the moment when Raymond knew he belonged.

Sign Up. SI NFL Newsletter. Get MMQB’s Free Newsletter. dark

“[There] was no way to, like, voice that in any way,” Raymond says, “but that’s what I had been working on.”

After the 2020 season, he became a free agent. Lions coach Dan Campbell called Raymond. Campbell mentioned Raymond’s return skills, and then …

“I saw this route versus the Colts, man,” Campbell told Raymond. “I was like, ‘Oh, this guy can play.’”

Raymond was stunned.

“What are the odds?” he says now.

Pretty good, actually.

Lions linebacker Alex Anzalone expected a contract extension this summer from the Lions, who gave him a $250,000 raise instead. / Junfu Han / USA TODAY NETWORK via Imagn Images

There are two kinds of franchises in the NFL. One has Patrick Mahomes. Everybody else is the other kind.

To make the Super Bowl, those other franchises generally need good health and a few good bounces. But mostly, what they need are chances: Keep playing in January, and eventually you’ll make it to February.

The Lions, who host the Packers on Thanksgiving, are 7–4 and in third place in the NFC North. In Week 11, the Eagles showed that a great defensive front can stymie the Lions’ high-powered offense—especially now, with star tight end Sam LaPorta out for the season.

But this year’s Lions have shown why the franchise has staying power. Winning consistently in the NFL requires more than just a scheme or even a nucleus of talent. You have to master the churn.

You have to constantly find fresh talent, incorporate new schematic concepts and adjust to your personnel—all while maintaining the identity that helped you win in the first place.

This is how tricky that can be. Lions linebacker Alex Anzalone, a terrific, multidimensional player, is the heart of the defense. Anzalone was a Saint when Campbell was an assistant in New Orleans, and when Campbell took the Lions job, Detroit immediately signed Anzalone. If you listed players who established the Lions’ culture, Anzalone might be No. 1.

This summer, Anzalone expected a contract extension. He didn’t get one. Anzalone vented publicly. The Lions held firm. Anzalone will turn 32 next September, and smart franchises don’t pay 32-year-old linebackers until they have to pay them.

The Lions added $250,000 to Anzalone’s 2025 salary, raising it to $6.25 million, according to various reports. They have signed almost every extension-eligible member of their core for far more money than Anzalone has made as a Lion: Aidan Hutchinson, Penei Sewell, Amon-Ra St. Brown, Jared Goff and Kerby Joseph.

You and I understand that age has to be a factor in these decisions. But we are not Alex Anzalone. The Lions effectively showed Anzalone that they might not need him next year, but they do need him now. These are the situations an NFL team has to nail—not just by making smart decisions, but by managing the fallout. Every team that wins a championship has essential players unhappy with their contracts.

Mastering the churn requires constant, relentless evaluation and re-evaluation. The Lions keep excelling because they know what they want and how to identify it, and don’t let anything else sidetrack them.

In the 2023 draft, the Lions used the No. 12 pick on running back Jahmyr Gibbs and the 18th on linebacker Jack Campbell, and critics said they didn’t understand positional value. On draft night in 2024, Lions general manager Brad Holmes wore a “Positional Villain” sweatshirt. This year, he wore one with HWS crossed out. The H, W and S stand for Height, Weight and Speed.

The message, all along: The Lions draft guys who know how to play football and live for it.

“The way we understand and process football here is a lot different than most teams,” defensive tackle Alim McNeill says. “There’s no secret to it. We understand that at a different clip than most people do. We all understand football, and football makes sense to us. So I think that’s really what it is. Football makes sense to everybody in here.”

Lions wide receiver Amon-Ra St. Brown doesn’t draw many pass-interference penalties because, according to his coach, he’s “so freaking strong that he can pull himself out of being held pretty good.” / Stephen Lew-Imagn Images

Raymond says the Lions’ locker room is filled with guys who “care to understand the why. We got all kinds of schematics and stuff going on. Care to study another night? Care to get another lift in?” This means coaches can adapt their scheme week to week and trust that players will execute it. One reason the Patriots won so much under Bill Belichick is that Belichick valued football intelligence.

McNeill makes another point, too: College players spend most of their time on campus, but “you get better here on your own in the offseason. If you’re working out and you don’t love the game, you’re not going to get better.

“Playing hard and giving your all 100% and being dialed in and detailed, that’s universal,” McNeill says. “You go to any building, and everybody’s got those same type of standards. When you come here, and your coach enforces it like that, it’s really nothing, because it’s already how you are, it’s already how you’re wired as a person.”

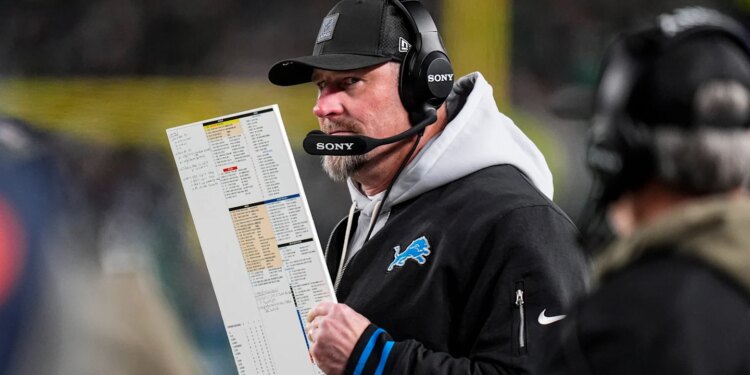

Mastering the churn means that when your two coordinators leave for head coaching jobs, as Campbell’s did last winter, you have to replace them and keep evaluating. Campbell hired John Morton as his new offensive coordinator, then stripped Morton of play-calling duties after nine games and started calling plays himself. That requires some guts, and the trust of the locker room, and Campbell has both—but mostly, it requires a head coach who is good at calling plays.

Campbell has received ample credit for his emotional intelligence, but he is also a brilliant football mind.

“He sees everything, man,” Raymond says. “He watches everything, every rep, every practice rep, on any drills. Everything he does has been thought 100 times over. He doesn’t do anything off just a whim. He’s probably thought about the rights and the wrongs of it more times than you can imagine in your head.”

Campbell also tells the truth. He did it with Morton, and he did it immediately after Brian Branch punched Kansas City’s Juju Smith-Schuster in September: “I love Brian Branch, but what he did is inexcusable, and it’s not going to be accepted here.” Last week, a reporter asked Campbell why the Lions don’t draw many pass-interference penalties. He could have lobbied for more. Instead, he said St. Brown is “so freaking strong that he can pull himself out of being held pretty good. Some other guys, one tug, and you really notice it.”

So many football coaches won’t tell the truth. Many of them are honest, decent people in their everyday lives. But professionally, they are wired so tightly that they avoid anything they can’t control. Campbell tells the truth, day after day, week after week. McNeill says even in the weight room, “We lift hard, we lift good. We don’t just do stuff that doesn’t make sense.”

If you watch the Lions on Thanksgiving, you will see St. Brown blocking like he is in danger of being cut. You will see Sewell mauling defenders like he is playing for a contract extension, even though he has already signed one. You will see Anzalone playing like he signed a contract extension, even though he didn’t.

You will also see a punt returner who rarely calls for a fair catch. Raymond is just like the rest of them: He constantly thinks there is a little more he can do.